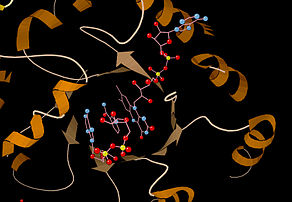

As part of a recent routine physical, I got some blood work done and tested positive for a mutation of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene, which encodes the enzyme of the same name. MTHFR is a key enzyme involved in the metabolism of folate, which is involved in the production of red blood cells. Genetic mutations may increase the risk for vascular disease.

The MTHFR enzyme

My father died of a heart attack when he was 51 years old, both of my grandfathers died of heart attacks before I was born, and my mother and maternal grandmother had pacemakers. Given the heart disease on both sides of my family, it wasn’t too big of a surprise to find out that I have a possible genetic marker for vascular or heart disease.

As a lifelong runner, I’ve spent a lot of time wondering if it’s possible to outrun bad genes. Will I die of a heart attack like my father, or will running protect me from that fate? Runner and author Jim Fixx, whose 1977 book, The Complete Book of Running became a national bestseller, may have been the first runner to bring national attention to running and health. When he died on the street during a run at age 52, it made national news and people, even doctors, started saying that running is bad for one’s health. In 2007, at the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in New York, 28-year-old elite runner Ryan Shay collapsed and died five and a half miles into the race. But both Fixx and Shay had underlying heart problems. Running did not cause their deaths. Fixx was a pack-a-day overweight smoker who ate cheeseburgers until he started running at age 35, and his father had a heart attack at age 35 and died of another one at 43. At the time of his death, Fixx was still eating cheeseburgers and had atherosclerosis, with a number of blocked coronary arteries. Shay had a cardiac arrhythmia due to an enlarged heart that was diagnosed years earlier.

No matter how much we run, our health is still heavily influenced by our genotype—the genetic makeup of our microscopic cells that lie deep within us and provide the code for who we are. But running can alter the way those genes express themselves and interact with our environment—our phenotype—to create our observable traits. And that’s where running holds its greatest power.

A couple of weeks ago, just a couple of months after finding out that I have a mutation of the MTHFR gene, I raced a mile in a track meet, and I strained my calf muscle. While it was concerning, I didn’t think much of it. I’ve been getting some calf strains lately with speed work and I thought that perhaps my age is affecting my calf muscles’ ability to keep up with my zeal for intense training and racing. Later that night, I started having severe chest pains. I couldn’t sleep because it hurt too much to lay down. Shallow breathing was fine, but the pain prevented me from taking deep breaths. If I didn’t have reason to believe it was something else, I would have thought I was having a heart attack. But I had reason to believe it was something else, because I’ve had this pain before, a couple of months after a bout of pneumonia two and a half years ago. Last time, I found out that the pain was caused by pleurisy—inflammation of the lining of the lungs. A CT angiogram—a fancy x-ray with intravenous iodine injection that acts as a dye to highlight the lungs’ vasculature—revealed a pulmonary embolism. I had a tiny blood clot in my right lung.

Now, over two years later, with another episode of the same pain, I had a feeling I knew what it was. Another CT angiogram revealed three pulmonary emboli and an ultrasound of my legs revealed a deep vein thrombosis in one of the veins in my calf. Clots sometimes develop in the large calf veins when blood pools in the legs and those clots can travel through the venous circulation to the lungs. To get to the lungs, the clot must travel through the right atrium and right ventricle of the heart. If the clot is large enough, it can get stuck in the heart, block blood flow, and cause a heart attack. If it passes through the heart into the lungs, it can be life threatening if the clot is large enough to occlude a major vessel. When the doctor gave me the diagnosis, my first thought was, “Am I going to die?” My second thought was, “Will I be able to run again?”

Luckily, the clots I have are small, small enough not to cause an immediate threat to my life. So I’m alive. I was put on anticoagulant to thin my blood and prevent more clots. Over time, my body will recanalize—form new vessels for blood flow around the obstructed clot sites. The body is very smart that way. When red blood cells run into traffic, your body’s construction workers create an alternate route.

Other than that mutation of the MTHFR gene, blood tests haven’t yet revealed that I have any genetic markers that predispose my blood to clotting, so I’m not sure what caused it. I haven’t been on any long international flights since June and, although I do sit at a desk a lot, I take breaks to walk around and try to drink enough water to stay hydrated.

I often wonder what I would do, how I would live, if something were to happen that would prevent me from running for the rest of my life. I’m not so sure that I could handle that.

It’s an understatement to say that runners hate to be injured or sick. It affects our lives in innumerable ways, none of which seem positive at the time it’s happening. Indeed, I have never met any other type of athlete or fitness buff, recreational or elite, who has hated being injured more than runners. I know a lot of people in the fitness industry—personal trainers, group exercise instructors, exercise DVD stars—and none of them get all ornery if they miss their workouts for a couple of days. But with runners, there’s a sense of impending doom if they can’t run.

For better or for worse, from the time I first started running and racing as an 11-year-old kid, my identity has been linked to being a runner. Running makes me feel powerful and fit. I feel like an athlete. When I’m fit, really fit, I walk with a swagger and with my head held high and full of confidence. Life seems full of possibilities. When something happens that prevents me from running, even for one day that wasn’t planned as a rest day, that identity is taken away. When that one day turns into a week or more, I get antsy, irritable, guilty and, yes, I even feel fat and out of shape. When what’s preventing me from running is health related, I feel vulnerable, scared, weak. I feel like the illness has taken away all of my power and vibrancy.

It may sound silly and irrational, but I feel like something is wrong with my life if I can’t run. Things just don’t feel right. I’ve been taken out of the community of runners, races passing me by like a train I was supposed to be on. Social media makes it worse. I see friends posting photos of their runs on Facebook, tweeting about their races on Twitter, while I sit at home missing out on the action. I’m not the same person when I don’t run. And everything else suffers. I sometimes even start to experience phantom pains in other parts of my body. All of a sudden, I feel a twinge in my calf or an itch in my hamstring. Luckily, this kind of thing doesn’t happen very often since I’ve always been one of those non-injured runners. But it’s happened enough that I know I don’t ever want it to happen again. Like the idle Porsche that doesn’t like to sit on the driveway, my body feels like it has to run to run right. Why buy a Porsche if you’re not going to drive it?

Although running carries a slight acute risk of a heart attack with its increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, the chronic benefits strongly outweigh the slight acute risk. If you have a very important meeting or event to attend in 30 or 40 minutes and you want to live for the next hour, don’t run. The tragedies of Jim Fixx and Ryan Shay remind us of the power of our genes. But if you want to live for the next 30 or 40 years, you should run on most days of the week because of the effect that running has on the expression of our genes.

I can’t wait to run. For now, however, as I wait to be healthy again, I’m grateful to be alive and grateful that, so far, I have been able to outrun my genes.

5 Responses to Blood Clots, Jim Fixx, and Outrunning Your Genes